South Mountain Legends

Ken Houldsworth tracks the trail of the legendary Snallygaster. The mythological winged creature, rooted in the culture of German immigrants, is said to terrorize South Mountain and the valley below.

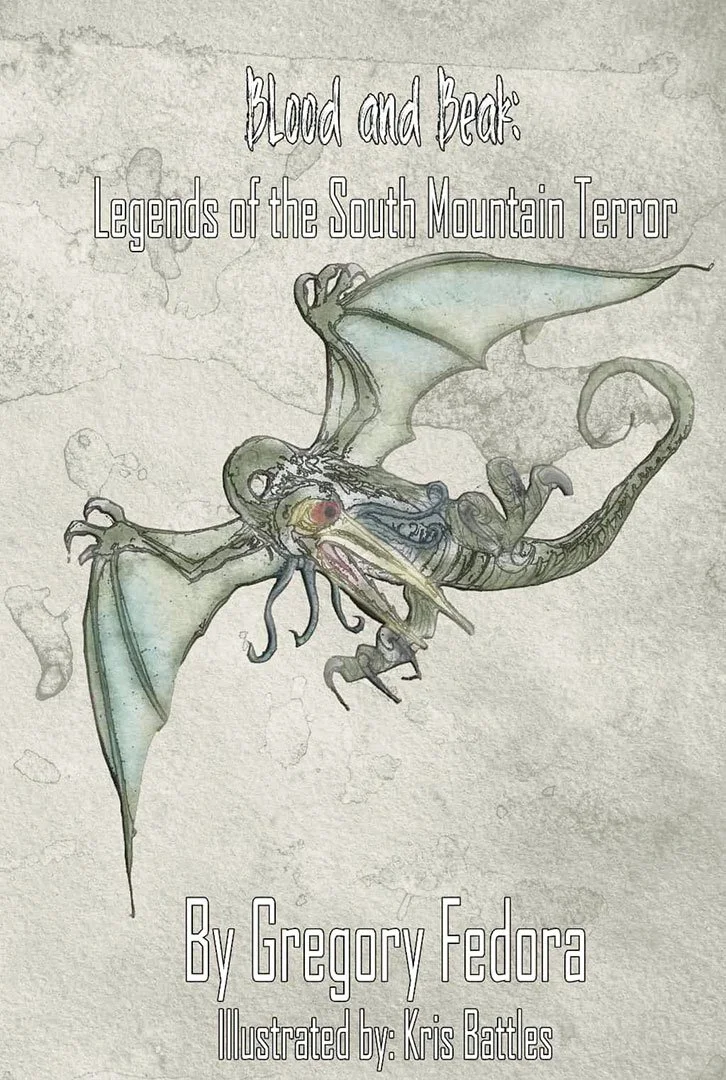

New book explores the Snallygaster and more

By Lisa Gregory

Beyond local circles, the myth of the Snallygaster may be one of Maryland’s best-kept secrets. “I remember when I moved here and first heard about it, I was surprised,” says Ken Houldsworth, a resident of Middletown who hosts the G Fedora’s Fedora Files podcast and authored the book series Happy Little Monsters. “You hear about Mothman, the Jersey Devil, Bigfoot [but not the Snallygaster],” he continues.

Houldsworth is the author of the new book Blood and Beak: Legends of the South Mountain Terror, a compilation of fictional short stories and poems about the Snallygaster. Each entry is based on his own research, including newspaper reports. “Sometimes it’s just a paragraph or two,” he says. “I thought why not embellish and create a whole story?”

The myth of the Snallygaster originated with German immigrants who settled at the foot of South Mountain in the 1700s. They called the monster Schneller Geist, meaning quick ghost. “It’s this ghostly spirit with wings like a dragon, and it’s quick moving and it’ll get you in the night,” says Houldsworth.

Through the decades there were those who claimed to have killed Snallygasters. Some even tried to make insurance claims that the Snallygaster had destroyed their barns or other property.

Houldsworth’s book Blood and Beak: Legends of the South Mountain Terror is a compilation of fictional short stories and poems about the Snallygaster, including a tale about the creature raising the ire of President Theodore Roosevelt.

“The moonshiners played into it,” says Houldsworth. “One of the things that became part of the Snallygaster legend was that it would make a whistling noise before it attacked. The moonshiners were saying that because the moonshine still would huff, producing a whistle-like sound as it boiled. So, to try and keep people away they would say, ‘Hey, that’s a Snallygaster.’ In that way they added to the myth.”

The disappearance of three local moonshiners earned the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt, according to Houldsworth. “It was in all the newspapers, even The New York Times,” he says. “It was a big deal and people were claiming a monster killed the moonshiners.”

Roosevelt, a staunch conservationist but also a big game hunter, decided to take down the Snallygaster himself, Houldsworth says. “He was going to come out to Middletown, out to South Mountain, and kill the Snallygaster for killing Americans,” he says. “You don’t go kill Americans when Teddy Roosevelt is around.” But before Roosevelt could set foot on South Mountain, the three “deceased” moonshiners were found.

“Some people think maybe [Roosevelt] actually came out,” says Houldsworth, “hunted it down and went with the story of, ‘Oh, they were killed by a distillery explosion,’ because it would be too much for Americans to think, ‘Oh my gosh, there’s a monster killing people,’ you know?”

Many people took precautions against the Snallygaster. In his short story The Witch-Binder of South Mountain, Houldsworth writes about Micheal Zittle, a purported wizard who lived on South Mountain in the 19th century. People would have Zittle “come out and put hexes on their land to keep the darkness from coming onto their property,” he says.

Houldsworth was able to locate Zittle’s final resting place in a cemetery in Boonsboro. “He felt that you should never profit off of magic,” says Houldsworth. “And he ended up dying in poverty. “

The short stories and poems in Blood and Beak follow a timeline from the original appearance of the mythical beast in local folklore to modern encounters. Houldsworth hopes to inspire curiosity about the monster, as well as Maryland history and folklore.

“I want to keep the myth alive and maybe even add to it, just let it continue to grow,” he says. “And maybe if people want to start researching and getting information on their own, that’s great, too. It keeps the people interested in it.”

He concludes, “The Snallygaster is Frederick’s story. It’s our story.”