This is the Price of Freedom

Hagerstown man honors Arlington National Cemetery by telling the stories of its history

By Lisa Gregory / Photography by Rick Gregory

Hagerstown resident Jim Garrett calls Arlington National Cemetery his family cemetery. And rightfully so. His own mother and father rest there as do both sets of his grandparents and their siblings. And when he adds in relatives through marriage the number totals 19.

Adding to his association with the cemetery, Garrett comes from a military family. “My father retired in 1966 and was the commander from 1962 to 1964 of the First Special Forces group,” says Garrett. Each Garrett child’s godfather was a general. “My brother’s godfather was a four-star general, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, head of NATO,” says Garrett. “My sister’s godfather was a three-star general.”

Then adding with a chuckle, “My godfather had only one star.”

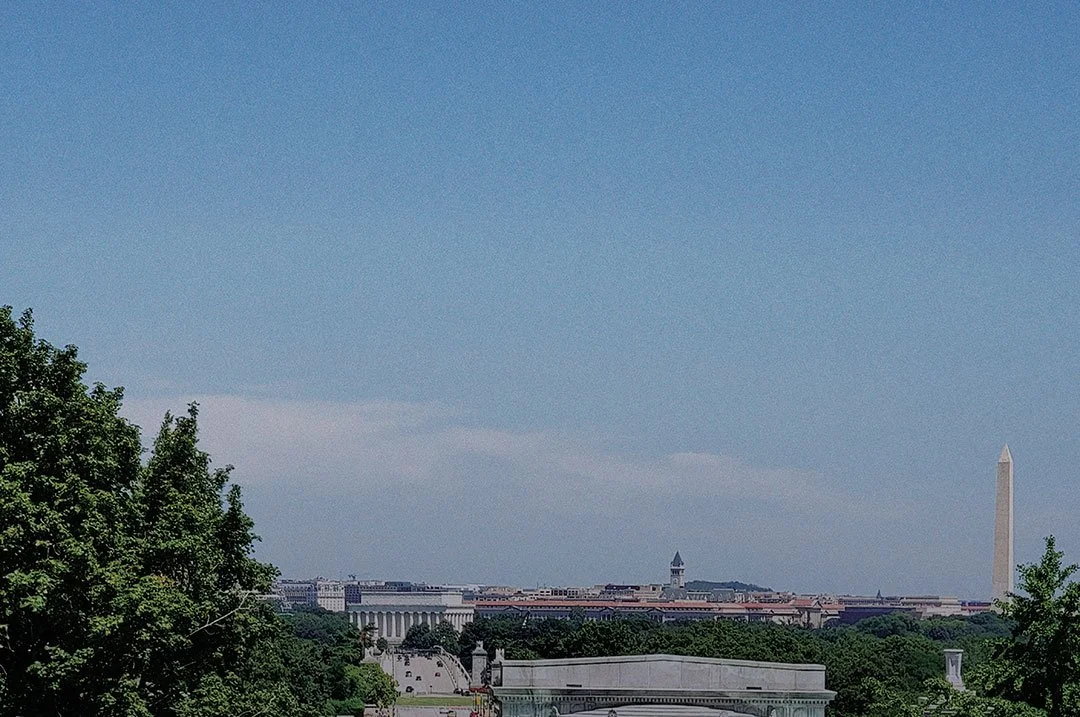

So, it is not surprising that he feels a special pull towards Arlington National Cemetery, which was established in 1864 on property previously owned by the wife of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee.

“This is the most sacred shrine,” says Garrett of the place where more than 400,000 are buried. “There is no other place in the world like it. And no one else in the world honors their dead like we do here.”

Garrett would know. He has worked at the cemetery as a historian as well as a tour guide. And his love of history has driven him to look deeply into the lives of those who have found their final resting place at the cemetery.

“The majority of people who walk into Arlington are there for two reasons,” he says. “The changing of the guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and President John F. Kennedy’s grave site.”

Both are important, he says, but there is so much more. “The stories I love are the ones people don’t even know about,” he says.

Garrett can recall the exact moment he became enamored with American history. “Because my father was originally a career military man, we lived in a lot of different places,” says Garrett. “We cycled back to Washington when I was in third grade.”

His days as a young boy living in Washington, D.C., were often spent in the company of his grandmother. “She would always take me down to the Smithsonian on Sunday morning,” he says. “I loved the American History Museum. It was my favorite.”

Hagerstown resident Jim Garrett at the site of his father’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery.

But it was a visit to a different place that made a lifelong impact. While visiting the Petersen House where Abrahma Lincoln was taken after being shot by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theatre, he saw the original pillow that had been beneath Lincoln’s head as he died. “It had a massive blood stain on it,” says Garrett. “It was something tangible. It was real. And that’s what got me on the history trail.”

Garrett, who attended boarding school at St. James School in Hagerstown, considered majoring in history in college. His father discouraged him. Instead, he went into the banking business, beginning in the early 1980s and retiring in 2013. But during all those years, Garrett, who would go on to marry and have a family, including fostering more than 30 children, never strayed far from his love of history.

“I volunteered at Ford’s Theatre,” he says. And he became an avid collector of historical artifacts. His most precious item is a prayer card from President Kennedy’s funeral service at St. Matthews Cathedral in Washington, D.C.

“It pulls at my heart strings,” he says. “That’s the moment our nation lost its innocence.”

After retiring from the banking profession, Garrett was free to pursue his passion for history more thoroughly. He went to work with a tour company focusing on historic spots. “I was a tour guide for two months and then became the tour guide trainer and the staff historian for Historic Tours of America,” he says.

As part of his work with Tours of America, he went to Arlington National Cemetery frequently. And when he heard that there was an opening for a historian there, he jumped at the chance. “The first thing they said to me was, ‘You don’t have a history degree,’” he says.

As the meeting and conversation progressed, however, it became obvious Garrett did know his history quite well. And more specifically he was well versed in the history of the cemetery. This was evident during a disagreement with the cemetery’s naval historian regarding the USS Maine.

“The stories I love are the ones people don’t even know about.”

“The rear mast to the USS Maine is there in Arlington,” he says. “The Maine was sent to Havana Harbor to safeguard American interests during an uprising. It was blown up and started the Spanish American War in 1898.”

The naval historian referred to the mast of the Maine at Arlington as the foremast. “I said, no, that’s the rear mast,” says Garrett. “We went back and forth. Then I said, ‘Look, the foremast is at the Naval Academy in Annapolis.”

They left the conversation at that.

“The next day he called me and said, ‘Yeah, you were right. And when do you want to start work?’”

Garrett began working at the cemetery in 2016 and was there until 2021 when he decided to cut back on his hours and take a lighter schedule. However, he still does tours for an independent touring company as well as continuing tours for Arlington Cemetery when called upon.

And on a recent sunny Saturday as he walked about the cemetery, pausing at different grave sites and telling stories, it was as if he was greeting old friends. Matt Urban is a favorite.

“Audie Murphy has traditionally been described as the most decorated soldier of all time,” says Garrett of the WWII soldier and recipient of the Medal of Honor. However, Garrett says that might not be the case.

According to Garrett, there is a theory that that honor goes to Lt. Col. Matt Urban, who also fought during World War II. “He was recommended for the Medal of Honor,” says Garrett. “His commanding officer did all the paperwork and gave it to a sergeant to take up to headquarters. The sergeant was killed in a Jeep accident, and the paperwork disappeared.”

Urban who was aware that he had been nominated, “never heard anything so he thought he didn’t get it,” says Garrett.

The changing of the guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington

National Cemetery.

The paperwork would be found three decades later. And it was also discovered that Urban was entitled to two more American commendations and a foreign commendation as well.

“Which put him one over Audie Murphy,” says Garrett. Though the debate continues.

Another soldier buried at Arlington, Gregory “Pappy” Boynton, also received the Medal of Honor under unusual circumstances. “The inspiration for the television series Baa Baa Black Sheep, Boynton received the Medal of Honor in 1944,” says Garrett. However, “He was shot down over enemy territory and was thought to have been killed in action. So, they gave him the Medal of Honor posthumously.”

But he wasn’t dead. “He was sitting in a POW camp in Japan,” says Garrett.

World heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, buried at Arlington, didn’t see combat, but he did do his part for the war effort after enlisting in 1942. He used his talent in the boxing ring to entertain the troops and boost morale with exhibitions.

“Louis entered military service under immense financial strain,” says Garrett. “His business manager had stolen him blind.” He was deep in debt to the IRS.

“He asked the IRS if they would forego the interest and penalties while he served his country,” says Garrett. “They said no.” In fact, after the war Louis would continue to struggle financially and even worked as a greeter in Las Vegas when his boxing career ended.

However, upon his death, he had someone in his corner. “His marker at Arlington was paid for by Frank Sinatra,” says Garrett. “So many people think of Sinatra as this tough guy, and here he goes and does something like this.”

Right next to Joe Louis is actor Lee Marvin of such films as “The Dirty Dozen.” Marvin was also a highly decorated U.S. Marine Corps veteran of WWII.

“It was his last wish to be buried next to someone famous,” says Garrett with a grin.

Veterans and service members make up a vast number of those buried at Arlington. But there are others there, too. For example, actress Maureen O’Hara is buried with her husband Brig. Gen. Charles F. Blair Jr.

And not all graves belong to Americans, says Garrett. British Field Marshal Sir John Dill is the highest-ranking foreign military officer buried at the cemetery. He found his final resting place at Arlington through the influence of his close friend Gen. George C. Marshall, who is also buried there. Dill was granted permission through a Congressional joint resolution approved by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“His granddaughter visited a couple of years ago,” says Garrett of Dill.

The grave markers are a who’s who in American history—from Tuskegee Airmen to astronauts such as John Glenn, the first American to orbit the earth, to polar explorer Robert E. Byrd.

“This shows the sacrifice that the United States and the people of the United States made to save the world in WWII. This is the price of freedom.”

Hagerstown resident Jim Garrett knows the history of individual soldiers buried at Arlington National Cemetery, including Matt Urban, perhaps the most decorated soldier of all time.

Then there is the monument which proves one can hold a grudge beyond the grave. Lt. Thomas McKee, who fought during the Civil War with the 1st West Virginia Volunteer Infantry Regiment, is buried with a large granite marker—large enough that it obscures the view of the grave behind it which belongs to Brig. Gen. Benjamin Franklin Kelley.

“McKee was Kelley’s aide, and it is believed that Kelley was an unduly harsh commander,” says Garrett.

McKee’s wife never forgave or forgot. Not satisfied that her husband’s tombstone fully overshadowed that of Kelley, she “added a marble angel to make sure it did,” says Garrett.

Arlington is an active cemetery conducting thousands of burials each year. While some come to visit the place as a historic landmark, others come to grieve a personal loss.

“I remember one Thanksgiving the family all loaded up and headed to Arlington to visit our relatives,” say Garrett. “There was a man sitting in a lawn chair by a grave eating Kentucky Fried Chicken all by himself. It was a moving moment.”

Of course, Garrett has had his own personal experiences visiting the graves of his family members, some more disturbing than others. Shortly after 9/11, Garrett discovered that the section where his parents are buried was closed. That section of the cemetery is near the Pentagon. “It was an active crime scene,” says Garrett, “and parts of the plane landed all the way over there.”

More than three million people visit Arlington National Cemetery each year, according to the cemetery’s website. Many are from other countries. Garrett says he understands why they are drawn to this place in the United States.

He recalls being asked to do a private tour for a young woman from Sweden a few years ago.

“It was a cold February day,” he says. “Drizzling. Just a miserable nasty day. And here was someone I would never expect to want to do a tour of Arlington, a young woman in her early 20s. Let alone in this weather.”

As they walked about the cemetery, he asked her why the visit was so important to her. Standing at a spot before row after row of white grave markers, she waved her arms before her, and said, “Because of this. This shows the sacrifice that the United States and the people of the United States made to save the world in WWII. This is the price of freedom.”